a tale of words and their power

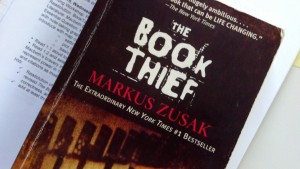

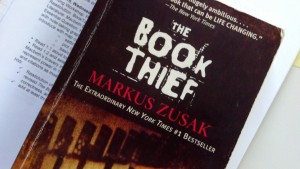

“The best word shakers were the ones who understood the true power of words. They were the ones who could climb the highest. One such word shaker was a small, skinny girl. She was renowned as the best word shaker of her region because she knew how powerless a person could be WITHOUT words” (446). This is the narrator, Death, speaking about the other main character of the book, Liesel Meminger, a young girl fostered to a German couple who need the money offered for her care. It’s pre-WWII Germany, and Liesl’s communist parents have been persecuted. Her younger brother dies on the way to foster care, and she must make her way alone in this new place. The story spins around the power of words.

Australian writer Zusak creates believable characters and dialogue that invite readers into a horrifying, harsh world of Nazi Germany because he balances the horror with moments of human tenderness and love, the best of the human condition. Stealing and reading books, playing and cherishing an accordion, keeping old promises, running, and hiding are the verbs of the story.

Here are some of the thoughts my students and I shared about this amazing book:

As readers, we are caught up in the empathy we develop for each of them, even Rosa, and the knowledge that because Death is the narrator, he is indeed intimately involved in their lives…this means some of their lives won’t last. Zusak manages to hold us in the suspense of their fates, with some foreshadowing in his clever chapter headings, and yet he also manages to make us feel deeply invested in their acts of tenderness and kindness even under these dire circumstances. –MM

Also, I think the book helped us to more precisely interpret the idea through the last year’s humanities class: how are we to live? More accurately, how are we to live even under extremely arduous and rapidly changing circumstances? For example, how are we to live under the situation Max was facing? Can we still work things out and take care of ourselves well while living in a cold, dark basement and always worrying about being caught, tortured, and killed? Do we have a strong and brave heart like Liesel so that even after the death of dear families and the person we love we can still keep our lives going? Does our mind have the strength to reject certain shaking but rotten words that could disrupt our regular lives so we don’t have to end up like these rationality-lost Nazis described in the book? And so on.—ZJ

Words free us, so powerfully illustrated by Liesel Meminger as she emerges out of conformity to define herself through her found, growing comprehension of words and figurative language in Markus Zusak’s, The Book Thief. Her insatiable thirst for words and books is lit and stoked by her foster father, Hans Huberman, whose fingers lift the notes of his accordion to hug Liesel in comfort, and whose midnight reading lessons foster Liesel’s love for words. In times of tumult and confusion, books are Liesel’s anchor. Upon her brother’s death, Liesel promptly finds The Grave Digger’s Handbook, a reminder leading to the events of her past, which commonly resurface throughout the book (it is very intriguing how the titles of the stolen books are so significant). This placement of frequent memories is an interesting way that provides a very real sense of hidden emotion in a character to the reader. Words empower Liesel in a time where conformity was the norm and opinion was often taken for fact when no other means of finding the truth were known. Hitler’s words may have easily been masked as truth instead of blatant opinion when people needed a leader. However, our small heroine comes to the truth that her only leader is her ability to formulate opinions and oppositions with the use of her own words.—NS

“It would then be brought abruptly to an end, for the brightness had shown suffering the way.”(358) This is a perfect example of the many sentences in this book that had a powerful effect on me. After I read this line, I immediately wrote it down in my notebook. Small things like well worded sentences, can really have tremendous effects on certain people. Words can free people, comfort people, or even outrage people. Personally, I found whenever something good happens in life, something bad almost always follows. The way Zusak described the “goodness” showing “suffering” the way, really made me think. It was such an interesting way of putting it.—EP

As we read a book there is always one character that we connect with more than the others, for me that character was Rudy. My favorite part of The Book Thief was reading about how Liesel and Rudy’s relationship unfolds, and how their friendship started off with a snowball in the face and ended with the greatest amount of love that a child can feel. Two passages that really stuck with me were the last time Rudy requested a kiss from Liesel and when Liesel was saying goodbye to Rudy. Each of the passages expresses how the characters view their relationship.

This passage when Rudy asks Liesel for a kiss shows how much he truly loved her and how unique their relationship was: “’How about a kiss, Saumensch?’ He stood waist-deep in the water for a few moments longer before climbing out and handing her the book. His pants clung to him, and he did not stop walking. In truth, I think that he was afraid. Rudy Steiner was scared of the book thief’s kiss. He must have longed for it so much. He must have loved her so incredibly hard. So hard that he would never ask for her lips again and would go to his grave without them” (303).—DVi

Another aspect that I liked about death as the narrator is how death seemed to not enjoy his job. I have always imagined death to be some evil, devil-like spirit who enjoys seeing humans suffer and die. The death depicted in this book was stressed, just like any other human trying to complete a tough part of their job, and Death also did not get joy from stealing the lives of innocent people. Not only was Death not as evil as I thought that Death would be, he also was very graceful and beautiful in the way he killed people. I was stuck by the passage when death said, “ I kissed the smaller ones goodnight”, because it felt so oxymoronic to me that Death could be depicted as something as sweet as a kiss goodnight (530). This new version of Death was very interesting to read about and it really gave me a new perspective on how I viewed death in general.—IE

The narrative voice was death, which was a surprising choice. Death could be such a depressing thing, but instead Death had a satirical tone. The author could have easily made death seem evil and it would have matched the book. The fact that death seemed to actually have a soul was an important contrast. Even Death itself was getting tired of the war: “How I’d have loved to pull it all down, to screw up the newspaper sky and toss it away. My arms ached and I couldn’t afford to burn my fingers. The re was still so much work to be done.” (336) The fact that Death had a strong voice and story added another tale as a background for Liesel’s personal life. At times, Death would pull itself away from the main story and take us out to see the effects that the war is having.—SS

We hope you choose to read the book and experience the power of the wordshakers.

Markus Zusak was born in Sydney, Australia, in 1975. Here is a link to a 2008 interview from the UK Guardian entitled “Why I Write” that provides a glimpse into Zusak: http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2008/mar/28/whyiwrite